Past DCRM Summer Intern Projects

2019 DCRM SUMMER INTERNS

PETER SANTOS

Sea Turtle Program, Department of Lands and Natural Resources

Preserving the CNMI’s Green Sea Turtles

Currently, an average of 12 nesting female green sea turtles visit the CNMI annually to lay their eggs. Over the past 11 years, 25 sea turtles have been illegally taken from beaches in the CNMI. According to an article found in frontiers in Marine Science (January 2018), Endangered Green Turtles of the Northern Mariana Islands: Nesting Ecology, Poaching, and Climate Concerns, poaching is currently the greatest threat to resident nesting sea turtles in our islands. Across the Pacific, sea turtles are hunted for various reason, such as jewelry, money and food. Because of this, the population of nesting green sea turtles has declined, which puts our coastal resources and coral reefs at risk. Green sea turtles are important because they promote biodiversity in our environment and provide income through the tourism industry. Sea turtles also play a major role in keeping our coral reefs healthy. Green sea turtles, which are the most common turtle species in the CNMI, feed on the algae that grow on corals. This increases productivity and allows coral reefs to thrive.

This summer, I was an intern at DLNR’s Sea Turtle Program. My internship project is part of an ongoing effort to protect CNMI’s sea turtle population and eliminate illegal poaching by collecting data on current nesting sites and spreading awareness of the threats sea turtles face. During my internship, we conducted outreach at a number of schools, as well as the Saipan International Fishing Derby, where we displayed stuff green and hawksbill sea turtles and preserved sea turtle hatchlings in jars. We also handed out educational materials such as hotline stickers and sea turtle coloring books. In addition to outreach, another way we help protect our sea turtles is through nightly beach monitoring. A typical night shift involved walking on the beach looking for turtle nests and tracks, and making sure previous nests haven’t been poached. I also assisted with nest inventories, which involved collecting data on the number of hatched and unhatched eggs in each nest.

This internship has increased my interest in sea turtle conservation, and has encouraged me to major in marine science at school. It will take many years to see the CNMI’s nesting sea turtle population recover, but with the help of the community, I believe it’s possible.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

NATALIE MONTANO

Environmental Surveillance Laboratory, Division of Environmental Quality

Testing for Bacteria in CNMI Waters

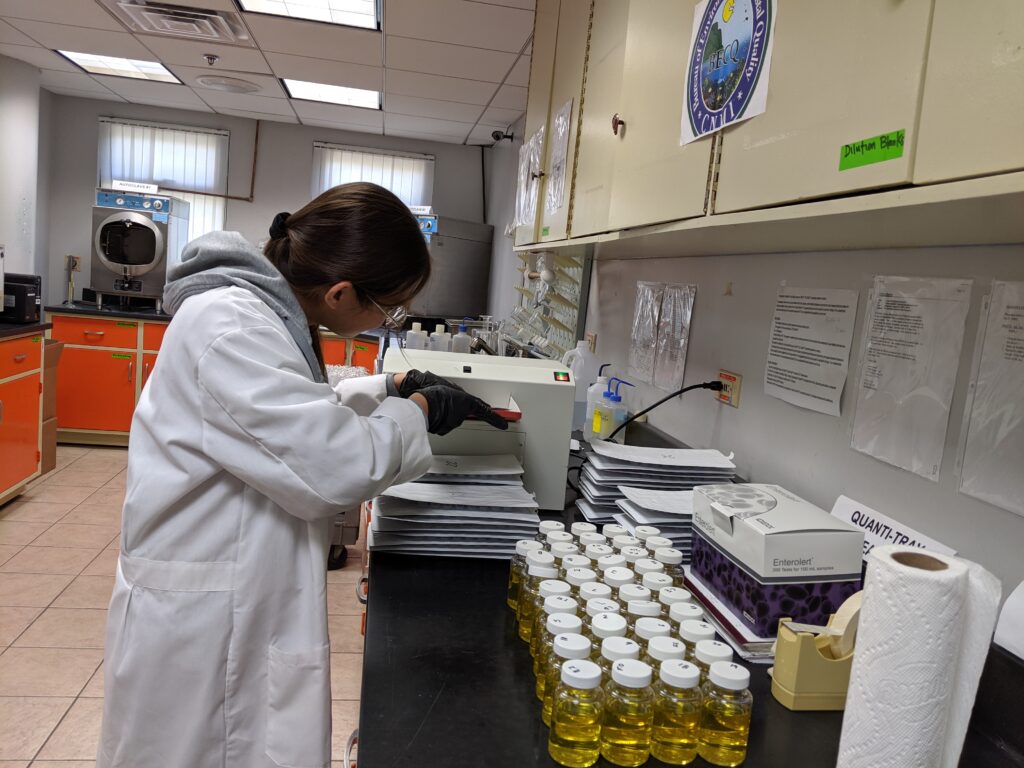

I began my summer working as an intern at the Division of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Environmental Surveillance Laboratory. I mainly assisted in the microbiology section where we analyzed marine water for enterococci bacteria and drinking water for total coliforms and E. coli. Total coliforms, E. coli, and enterococci are all bacteria found in fecal matter.

Working in the laboratory, it became my main project to analyze marine water to quantify and monitor the microbial quality of the beaches on Saipan, Managaha, Tinian and Rota, and to assist in testing drinking water to maintain safe drinking standards.

The first step for each water analysis was to collect water samples to bring to the laboratory for testing.

Marine water samples were collected from CNMI beaches by the DEQ Water Quality staff. Once the samples arrived, we diluted them and added enterolert media to each sample to detect enterococci bacteria. Afterwards, the samples were incubated for 24-48 hours. If the sample fluoresced under UV light after the incubation, then it was positive for enterococci bacteria.

Drinking water samples were collected by the DEQ Safe Drinking Water staff from clients. In the lab, we added Colilert-18 media to each sample to detect total coliforms and/or E. coli. The samples underwent pre-warming for about 7-10 minutes then were incubated for 18 hours. The results were achieved by comparing the samples with comparator (container of water that contains total coliforms and E. coli for reference). Here are the possible ways to determine the results:

~ Sample has no color/color is lighter than the comparator and is not fluorescent = negative for total coliforms and E. coli

~ Sample is darker than/equal in color to the comparator and is not fluorescent = positive for total coliforms only

~ Sample is darker than/equal in color to the comparator and is fluorescent = positive for total coliforms and E. coli

To alert the public of the findings of the marine water analysis, a Public Beach Advisory (red flag) is put out on the CNMI DEQ web page if the water quality results exceed the CNMI Water Quality Microbial Standards. Test results are also provided to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Congress, and the media. Results for drinking water samples are reported back to the client.

E. coli in drinking water can harm people if consumed, and significant amounts of fecal bacteria can hurt the economic and recreational value of marine waters. In addition, the presence of total coliforms, E. coli, and enterococcus bacteria “is indicative of the potential presence of other more pathogenic organisms which are a danger to human health” (Price and Wildeboer, 2017).

Water analyses are crucial for marine water quality assessments and for maintaining a healthy community. Prior to this internship position, I had little knowledge of the significance of bacteria in our aquatic resources. It is only through my experience in the laboratory that I learned of the importance of water testing and the effects of these bacteria (enterococci, total coliforms, and E. coli) on our community and environment.

Works Cited:

Robert G. Price and Dirk Wildeboer (July 12th 2017). E. coli as an Indicator of Contamination and Health Risk in Environmental Waters, Escherichia coli – Recent

Advances on Physiology, Pathogenesis and Biotechnological Applications, Amidou Samie, IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/67330. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/-i-escherichia-coli-i-recent-advances-on-physiology-pathogenesis-and-biotechnological-applications/-i-e-coli-i-as-an-indicator-of-contamination-and-health-risk-in-environmental-waters

____________________________________________________________________________________________

DIANNE PABLO

User Capacity Assessment of Prime Tourist Sites (UCAPTS), Division of Coastal Resources Management

The Cost of Our Lagoon

Polluted waters and overcrowded beaches. Sound too familiar?

The island’s white sandy beaches and offshore coral reefs are some of its most famous features that hold symbolic value to locals and tourists alike. Because of Saipan’s beauty, it is no doubt that the tourism sector is a primary contributor to the CNMI economy. But to what extent will these natural resources be exploited before they completely deteriorate?

Under the Division of Coastal Resources Management Internship, I worked on the User Capacity Assessment of Prime Tourist Sites project. This study aims to determine management practices for sustainable development of the tourism industry. By understanding the predominant and increasing pressures within the industry, capacity limits can be identified and better decisions can be made to maintain the environmental health of these sites.

Within the UCAPTS project I was tasked to create an economic valuation of the marine sports industry in Saipan, using addendums from Marine Sports Operators (MSO) permit renewal applications in 2019. MSO provided a value for each permitted activity they offer to clients. Some of the activities included were banana boating, jet skiing, parasailing, wakeboarding, snorkeling, SCUBA diving, floaters/aqua cycle, kayaking, stand up paddle boarding, windsurfing, and Managaha transfer/lagoon tours, amongst others.

Spatial data was generated through ArcGIS and ultimately portrayed the different areas of operation. This was my favorite part of the study because not only did I get to see which areas contain the most activity, I also saw which of those areas generate the most value for the CNMI. The total was $3,822,019.19; this number coming directly from permitted marine sports operations alone. Not including previous coral ecosystem valuation studies, this estimate should be considered a conservative value for the CNMI. Generating this number can help other state agencies and legislators make informed decisions when managing the CNMI’s most valuable resources, such as the Grotto.

The conflict between financial insecurity and environmental degradation proves that traditional investments in a strong economy do not always contribute to a healthy environment. This shows how “the two are strongly interconnected, both of which are equally important to our growth and wellbeing.”* Tourist congestion is not only about the number of visitors but about the capacity to manage them. The challenge is to find methods to accurately measure and valuate these ecosystem services. By identifying the economic value of our marine ecosystems, stakeholders and policy-makers will begin to understand this crucial relationship. Such information can support wise long-term decisions, which is what we all need – government leader or not – in preserving our coastal resources.

*Works Cited:

Tourism value of ecosystems in Bonaire (pp. 1-7, Publication). (n.d.).

____________________________________________________________________________________________

ALDEBERT DELEON GUERRERO

Geographic Information Systems, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Informed for A Brighter Future

For a handful of years now, our tiny island of Saipan has been a popular location for a myriad of development projects thank to its ideal paradise destination, steady tourism industry, and not to mention its natural beautify and allure. In the near future, a few of these development projects are expected to turn into completely refined hotels, resorts, townhouses, and even a casino! With that said, it is evident that our island continues to experience change every single day. It is absolutely vital to obtain information on these developments in order to better understand their effects on the environment and society. Regardless of size, these development projects have the potential to stunt Saipan’s growth and of course, deplete its finite resources.

As an intern under the Planning section for the DCRM Summer Internship Program, my project, which takes place at BECQ, involves the creation of an interactive dashboard that contains key data taken from permit applications for development projects on Saipan. This dashboard is intended for the public and other agencies to view the data geospatially. With the use of a reliable PC and software tools such as Microsoft Excel and ArcGIS, my project becomes much easier to accomplish. When carrying out this project, I follow a general set of steps. First, data is gathered from all the permits issued by DCRM on all development projects and entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Second, the spreadsheet is then exported tot he ArcGIS software to display the locations of the projects. Third and lastly, the data is uploaded online so that it can be used to generate an Operations Dashboard (an online app used to build the interactive dashboard). The dashboard will contain an interactive map, charts, and indicators that provide information on Saipan’s projects and their permits. Currently, only Major and Minor Sited permits issued for Saipan are available and you can expect to see th launch of this dashboard by the end of September 2019. This is a living application, so more data will be added as mroe development projects are permitted.

Dale M. Lewis, a GIS expert, strengthens the purpose of my project when he says: “maps composed of easily recognizable information about land-use issues affecting the welfare of local residents and their natural resources would faciliate communal societies to make technically improved land-use decisions within a community.” As I near the end of my internship, I truly hope that this dashboard will prove to be a great asset to the public and other agencies. Its’ significance lies in its’ ability to help others easily gather information on development projects and as a result, help them better understand how these developments affect the resources of our previous island, as well as its’ people. Hopefully, with a greater understanding of these projects and their avoidable impact, we, as a community, will be one step closer to a future devoted to a balance of continued growth in the development and protection of our island home.

Works Cited: Lewis, Dale M. “Importance of GIS to community based management of wildlife: lessons from Zambia.” Ecological Applications 5.4 (1995): 861-871.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

NEILDINO TAISACAN

Coral Reef Initiative Education & Outreach, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Coral reefs in the CNMI are threatened by land-based sources of pollution. Nonpoint source pollution is a leading cause of coral reef degradation in the CNMI. Water quality is impacted by urban runoff, failing sewage systems, unpaved roads, farms, land clearing, and development. Stormwater that drains tot he ocean carries sediment and excess nutrients, which smother coral and cause algal blooms, impacting reef health, like the Great Barrier Reef, which as been experiencing for decades a deterioration in their ecosystem due to land-based pollution.

In recent years, more than half of Saipan’s shoreline has been marked “red flag” or unsafe to swim in on a chronic basis. Each of the sites has measured high in the bacteria level more often. As a 2019 DCRM Summer Intern, I conducted field studies with the Water Quality Monitoring and Nonpoint Source Pollution team. We would go out with sample bottles and collect water samples from sites around the island and Managaha that would be brought to the DEQ Laboratory to be tested. The results are able to inform the public whether the location sampled is red (not safe to swim) or green (safe to swim) flag. In addition, I had the opportunity to do a stream assessment at Dougas stream located in Tanapag where we collected data on the stream conditions such as the embeddedness of the rocks, the flora and fauna, and if any contaminants and pollutants were present.

Initiatives like the Garapan Clean Water Campaign encourages businesses and the community to prevent land based pollution from reaching the lagoon. I assisted in getting up to 13 businesses to participate in an Ocean Friendly Property Pledge, which is both a resource guide and good way for businesses to advertise their best practices. I helped to raise awareness within the community about the issues in the environment. I conducted door to door outreach with Micronesia Islands Nature Alliance (MINA), looking for common environmental violations in the area. I also had the opportunity to be involved int he Garapan Storm Drain cleanup where I tracked the amount of sediment they collected during the clean out. They removed a total of 20-30 cubic yards of sediment.

To expand on these initiatives, I also placed eco cards next to ocean friendly products at all the major stores on the island in an effort to promote ocean friendly practices. Another highlight of this internship was the opportunity to travel to Tinian to help people of the island understand how important their watershed is and ways they can help protect it. Through all the work expereience, I have gained so much knowledge on how much we have an impact on our environment, how storm water pollution affects our nearshore waters and coral reefs.

It has shown me that the issue must be prevented and has inspired me to help others do the same. The skills I have learned and will take with me after the internship is to take the initiative on protecting our environment by preventing these land-based pollution from entering our ocean. My time as an intern from DCRM and DEQ has been a great adventure and I don’t regret a minute of it.

Works Cited: Frederieke J. Kroon, Peter Britta, Schaffelke, Stuart Whitten (2016) Towards protecting the Great Barrier Reef from Land Based Pollution Global Change Biology (Volume 22, Issue 6) [accessed August 15, 2019] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gcb.13262

____________________________________________________________________________________________

ANELA DUENAS

Coral Reef Initiative Marine Monitoring, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Protecting Our Reefs

Coral reefs provide many benefits for the community including food, shoreline protection, and tourism. Protecting our marine life in the CNMI is essential for present and future generations. The CNMI Marine Monitoring Team (CNMI MMT) are our doctors of the reef. They collect data yearly on 52 long-term monitoring sites across Saipan, Tinian, and Rota. These sites were selected based on association with management concerns such as runoff, sewage outfall, and urban development. They were also selected based on management actions such as watershed restoration efforts and marine protected areas (MPAs). This is to determine the current status and changes the reef has throughout the years. Without this information, immediate action cannot be taken to prevent damages to our reef.

CNMI MMT follows a procedure that requires scuba divers to gather data at a depth of 25 meters. They collect data by taking photos each meter along five transect lines per site. The transect lines used are 50-meter ropes with markings used to indicate every meter. These photos are then taken back to the office and transferred into a Coral Point Count with Excel extensions (CPCe) system. 150 photos are uploaded per site. Each photo contains five random points placed by the CPCe and are identified by CNMI MMT biologists. They identify the genus of coral, algae, sponges, and invertebrate. Having randomized points allows the data to be accurate. After completing a site on CPCe the data is transferred into the database with data from previous years along with data from different sites.

The data allows the CNMI MMT to observe changes in the coral reef and take proper action needed to protect and conserve it. This is done through MPAs and restoration projects. The action taken is essential to allow our coral reef a healthy growing environment. Without these protection efforts, we risk decreasing our food, shoreline protection, and tourism.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LAURINA SEBAKLIM

Fisheries, Division of Fish & Wildlife

What is Fish Tagging in the Marianas?

You are probably wondering, what is fish tagging? Why do we tag fish? Why is it important? Let me share a little bit of how and what I’ve learned that is an important program for fisheries in the Northern Mariana Islands.

I was selected to be part of the 2019 DCRM Summer Internship. The Division of Coastal Resources Management teamed up with various natural resource agencies here on the island to help out with keeping our ocean healthy. I was fortunate to be part of the Division of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) under the Fisheries Section. My team and I had many projects during my internship. We had fish tagging, crown of thorns monitoring, and buoy missions.

Fish tagging was our main focus. When the weather is right, we take our boat out into the lagoon and start on with our rod and reel. Usually, it takes a while to catch just one fish. When we finally have a catch, we get it into our little bucket and weigh them out. After weighing the fish, we tag it. We use a fish tagging gun to shoot the tags near the top of the fish spikes. After inserting the tags, we let the fish off into the ocean.

We don’t just tag any fish here in the Marianas. Our main targets are the Emperor species and the Carangoides species, also known as Tarikitu. We focus mainly on these species because these species are very valuable food fish to our locals. Fish tagging is important because this helps DFW track information on fish migration, how fast they swim, and their growth. Fisherment are encouraged to call DFW at 664-6000 if they catch any of these tagged species so that we can input data of how many tagged fish are caught.

My overall experience with this internship was better than expected. I had the opportunity to learn fisheries in depth and the importance of CNMI’s coral reefs. I encourage all students to take advantage of this great internship. It has helped advance my interest in marine science.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LANCE TUDELA

Enforcement, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Violation = Citation

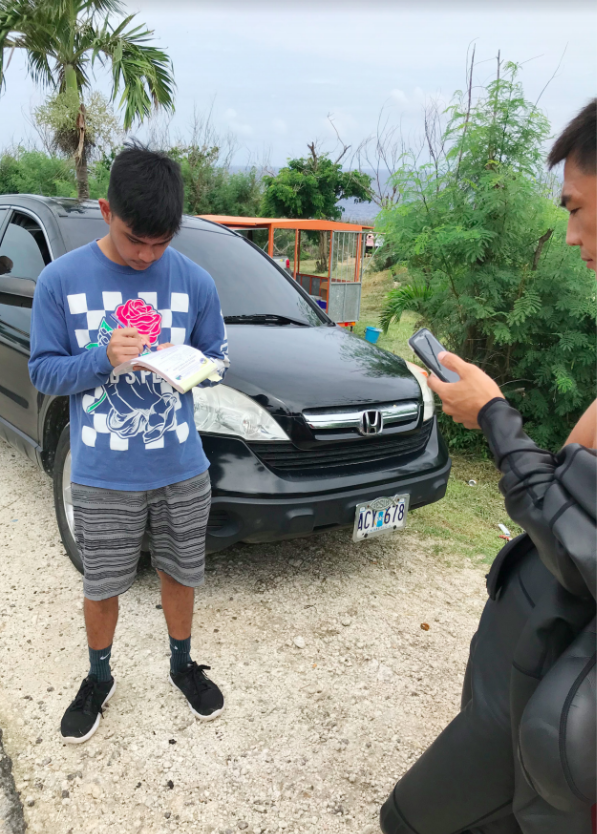

While waiting in the beaming sun with Enforcement Officer Pangelinan and conducting our routine inspections, a tour guide with an expired permit was not able to present his Marine Sports Operator (MSO) permit card. It is mandatory that all MSOs have their permit cards on them at all times while operating. Tour guides should know this is part of their permit conditions.

Being an enforcement officer requires you to be patient, especially with some of the tour guides that can’t speak English. The tour guide at Grotto was giving us a hard time saying that he had a permit to operate, but he only had a picture of an expired permit contract. We handed the tour guide a citation and told him he could not operate until he renewed his permit.

The 2019 DCRM Summer Internship was my first job ever. I learned the importance of accountability and what goes on behind the scenes of a government agency like the Division of Coastal Resources Management (DCRM). I was assigned to be an intern under the DCRM Enforcement section, where I had the opportunity to work closely with other enforcement officers.

For my assigned project I had to create an educational flyer on the DCRM permit conditions for the MSOs. MSO’s are tour companies that utilize our lagoon for recreational activity. From snorkeling to jetskis, these are forms of marine sports, and these marine sports can impact our valuable coastal resources if not well regulated. For example, a motorized permit for a jetski company has a special location where they are allowed to operate.

The overall purpose of my project was to create awareness among MSO’s on the importance of permit conditions. DCRM wants the MSO’s to follow the permit conditions to mitigate impacts of marine sport activity. Unpermitted MSOs are encouraged to go through DCRM’s permitting process because it teaches the company how to operate with best management practices. MSOs who do not comply with DCRM Permit Rules & Regulations can impact our lagoon. After all, the rules are there in the first place to keep the company and our ocean safe.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

ESTHER HUH

Micronesia Islands Nature Alliance (MINA)

Bring Back Our Trees

What are we without trees? Trees can thrive in salty places, reduce soil erosion and runoff, enhance respiratory health, provide a habitat for wildlife, combat global warming, and keep our coral reefs alive by lowering temperatures and rooting soil in place preventing sediments from washing into the sea. Throughout the years, we have witnessed the sea levels rising, warmer summers, increasing typhoons, and the corals bleaching faster. Corals are bleached due to increased water temperatures and ocean acidification. The oceans are suffering from an excess of carbon dioxide, which hinders the production of coral skeletons and degrades fish habitats. As a DCRM Intern at the Micronesia Islands Nature Alliance (MINA), I learned that we must always take care of our environment. I admit that i did not think too much of trees before I interned at MINA, but through it I learned the importance of being aware of current conservation efforts and that it is never too late to get involved.

A similar situation can be seen on the island of Kotoka in Tanzania. According to National Geographic’s Sarah Gibbens, Kotoka, with limited resources, was at risk of losing food and water with fisheries and rivers depleting (Gibbens, 2018). Residents came up with a plan to plant appropriate trees to gain new crops and protect the residents from future storms. Like Kotoka, our future depends on how we overcome challenges, and one solution is to plant native trees, even more so for their medicinal use and cultural significance.

This year, MINA launched “Bring Back Our Trees (BBOT),” a campaign that started in response to Super Typhoons Soudelor and Yutu, wherein numerous trees were damaged, uprooted, or destroyed. MINA’s goal was to revegetate Saipan’s shores with native trees to replace those lost in the typhoons and prevent further sedimentation and degradation of our reefs. So far, as a community, we have planted 529 trees on Saipan and 74 on Tinian, exceeding the original goal of 300. The program is funded by the Department of Interior (DOI), with support from community volunteers and lcoal agencies such as the Saipan Mayor’s Office, DFEMS, CNMI Forestry, NMC CREES, CNMI BECQ, Tinian Mayor’s Office, Tinian Fish & Wildlife, and Furey and Associates, LLC. The Tasi Watch Community Rangers maintain the trees’ survival by watering weekly.

As a summer intern, I supported this campaign by studying the trees at our sites through reading materials such as the Common Flora and Fauna of the Mariana Islands by Scott Vogt and Laura Williams, and Island Ecology & Resources Management: Commonwealth of the Nothern Mariana Islands by John Furey et al.,. These books helped me identify the local and scientific names of the trees while I took inventory and recorded the number of trees and species planted at the pre-selected sites. We also monitor the new trees planted and encourage the public not to run over, step, or uproot them. In a few years, we will witness the growth of the trees and see how they are providing a healthy and safe environment for us all.

Without our natural resources, our island would not be what it is today. With gratitude and a sense of obligation, we hope you find a desire to return the favor to our land and protect it, by starting with protecting the trees that have been planted through BBOT, planting more trees in your backyard, and getting involved with other efforts to support a resilient natural environment.

Works Cited: Gibbens, Sarah. “This Island Was on the Brink of Disaster. Then, They Planted Thousands of Trees.” National Geographic, National Geographic, 20 Dec. 2018, www.nationalgeographic.com.au/nature/this-island-was-on-the-brink-of-disaster-then-they-planted-thousands-of-trees.aspx.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

LORIANN JOHN

Shoreline Monitoring Program, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Targeting Shoreline Areas Subjected to Accretion and Erosion

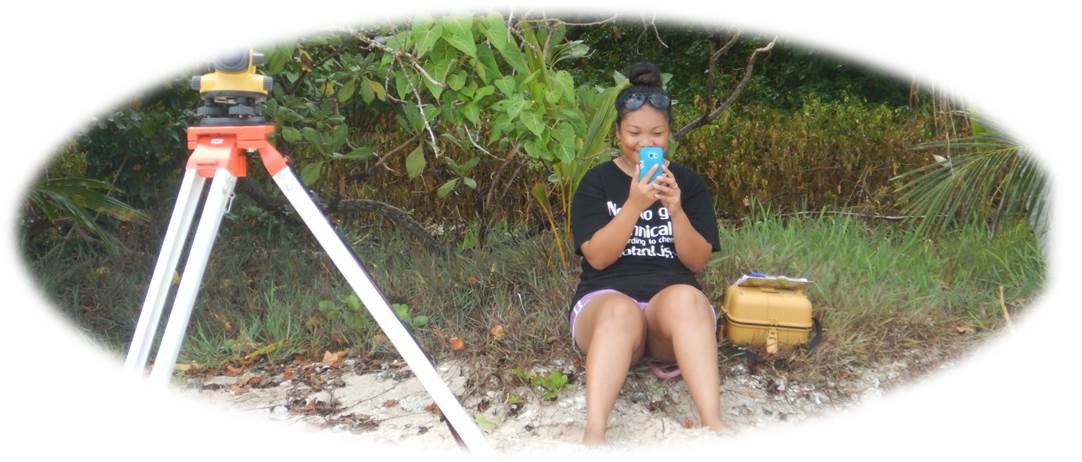

The Division of Coastal Resources Mangement (DCRM) Shoreline Monitoring Program began in 2016 with the goal to understand and predict how fast our beaches can grow and shrink by recording measurements over time and observe the trends of erosion (sand loss) and accretion (sand gain) depending on which cardinal direction the wind and waves toward. With data that’s being collected overtime, we can see which beach’s sand are stable, increasing, or decreasing.

Monitoring activities are conducted bi-annually across Saipan’s west shoreline. This program is run by a team of three people who each play an important role in collecting and analyzing data. The first person looks through a Berger level, a tool that measures elevation from the head stake/starting point of a transect to the beach toe. The second person moves a 16-foot aluminum ruler along the transect line, stopping every 10-feet for the first person to take another measurement. The third person, the recorder, is responsible for accurately recording the data, including measurements, dates and time. Other tools we use to accomplish the project are a data notebook, camera, Garmin GPS unit to find the head stakes or input a new location, and a 100-feet measuring rope or transect line that we layout along the shore to be profiled. With these tools, we can accomplish exact measurements of each beach to compare with the previous year’s data and analyze the changes.

There are usually two to three head stakes at each beach, but some can get lost. For instance, after a super typhoon hit Saipan in 2018, some of the head stakes were gone. We use pictures we’ve taken or GPS points to find our head stakes. It is important to start at the same head stake every time because starting at a different head stake will change the slope measurements and we want to obtain readings from known elevations.

Anfuso, Giorgio & Bowman, Dan & Danese, Chara & Pranzini, Enzo. (2016). TRansect based analysis versus area based analysis to quantify shoreline displacement: spatial resoluation issues. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment.

Works Cited: Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308271956_Transect_based_analysis_versus_area_based_analysis_to_quantify_shoreline_displacement_spatial_resolution_issues

____________________________________________________________________________________________

SHANNON SASAMOTO

Coastal Zone Communications, Division of Coastal Resources Management

Conversations In Conservation

My name is Shannon Tudela Sasamoto, 2019 DCRM Summer Intern working in the Coastal Zone Communications section. Being part of this division means creating consistent and accurate outreach materials available to the public. Essentially, it is connecting with our target audiences to ensure they are doing their part in taking responsibility not just for our islands, but our whole planet. Part of the role of outreach is creating methods we can use to encourage our community to act in ways that protect and preserve our environment. Some of the materials I’ve helped to create include stickers, social media posts, posters, as well as outreach activities for direct communication with the public.

The importance of education and outreach is to translate scientific data and technical language into materials that are easily understood by everyday citizens. In other words, we are the middlemen between the scientists and the community – interpreting and producing informative material that inspires and motivates the public. Just as a scientist’s job is important, so are the efforts from our local community to understand the work towards a better environment for everyone.

Education and outreach doesn’t just stop at our local community, it extends towards tourists, marine sports operators, tour operators, private landowners, and private developers. These target audiences are just as important as our local community because those who have touched our soil and swam in our oceans have the same responsibility to care, respect, protect, and preserve our environment. This is simply because our lands and oceans do not belong to just us, but to our ancestors and future generations as well.

Our environment is the sole link and connection to those before us, sharing the trees they once used for the construction of their huts, the reef that still provides us food and habitats for marine species, and the minerals that was once used for the creation of our symbolic legend and figure, the latte stone. The nature surrounding us defines the strength, pride, and culture of our home. Respecting our environment means respecting our ancestors and realizing that there is so much historical and cultural significance beneath our feet.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2016 CRI Summer Internship Projects

Lagoon Habitat Mapping- Aldebert Deleon Guerrero and Katelynn Delos Reyes, NOAA Interns

The Coral Reef Internship has given me the invaluable opportunity of allowing myself to gain knowledge and continue to grow as an individual. Working under NOAA for the past two months was an absolutely exciting and delightful experience. Throughout the course of the internship, I was given the task of constantly going into the Saipan Lagoon and navigating to a variety of habitats in order to update its’ benthic map. Over the course of two months, I have had the greatest pleasure of meeting wonderful people as well as getting hands-on experience in the area of coastal resource management. As a result of participating in this internship, I have decided to pursue a career in natural resource management. I heavily encourage other students to take this opportunity when available to them in the future!- Aldebert Deleon Guerrero

As a part of NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program project for the CNMI, we collected data by ground-truthing satellite imagery of the Saipan Lagoon. Our NOAA mentors provided us with all the equipment needed, this includes: a GARMIN GPS device, meter quadrat (made by interns), PAM safety float, Reel for anchoring, Canon camera, meter stick for measuring depth, our individual snorkel gear (provided by BECQ-CRI), and customized data sheets (made by Matt Kendall). A set of data points were given to my partner and I to help collect data within the intertidal zones where the depth is less than 4 feet. This project is led by Matt Kendall and his partner Bryan Costa who are currently on island to continue collecting data farther out in the lagoon. The information from this data will be used to create an updated benthic habitat map to track changes in the lagoon over time, as well as create better monitoring and management decisions for the Saipan Lagoon.-Katelynn F. Delos Reyes

Seagrass Resilience- Zia Buniag and Michelle Kautz, CNMI Marine Monitoring Interns

My name is Michelle Kautz and I was given an amazing opportunity to be an intern under the BECQ Marine Monitoring Team. This summer I have been studying and surveying our local sea-grass beds and what common invertebrate, macro-algae, and sea grass species are found here in the CNMI. Going out almost every week to do surveys while snorkeling, was the best part of this internship because I believe that hands-on work is the best way to learn. Other than the snorkeling, the other group activities such as turtle tagging, Laolao bay watershed field trip, and outreach to our local children, made me realize how important it is to have knowledge on what is happening here in the CNMI. The biological research itself is not the only thing we can do; outreach is just as important as scientifically studying the environment.

Besides going out to the beach, data recording and lab work play a large part of the internship. Processing the samples we collect from the field takes time, and we must make sure that we record everything accurately and as efficient as possible. Other than the surveying of sea grass, my partner Viktoria Buniag and I go out to reef dive spots and check for any indications of coral bleaching. Coral Bleaching is beginning to become a huge problem here in the CNMI. Bleaching indicates that the coral is stressed because of the conditions it is living in. Climate change plays a huge role of coral bleaching because warmer temperatures can decrease the calcification and growth rates which can link to ocean acidification. Because of this internship I have gained knowledge through witnessing these occurrences of coral bleaching in our reefs and how sea grass beds can help prevent them from dying off. -Michelle Kautz

My name is Zia and I fortunately had the chance to work with the Marine Monitoring Team this summer. I spent most of my time under water, which was the cherry on top! During my internship I learned about the types of seagrass we have, and about various algae and invertebrates that are common in our lagoons. I also learned about the importance of seagrass and how great they are for our environment and coral reefs. Seagrass provides nursery areas for many marine organisms, prevents shoreline erosion and acts as a filtering system for the coral reefs. Seagrass acts as the first line of defense for coral reefs they prevent sediments from getting to our coral reefs. Sediments can reduce the light that reaches the corals and if a great amount of sediment reaches the coral reef it may bury them. Seagrass and coral reefs are a major part of our island ecosystem so we must do everything we can to protect them. –Zia Buniag

Shoreline Monitoring and Beach Profiling- Teisha Camacho and Kiana Palacios, DCRM Planning Interns

The goal of the Shoreline Monitoring program is to monitor areas of coastal erosion and accretion, which is also known as beach loss or beach growth. We monitor the Western beaches from south to north including the Island of Mańagaha which has five sections to it. We also collect data to see the change in sea level over time and create a beach profile for all the Western beaches and the Island of Mańagaha. Teisha Camacho, an intern under the Coral Reef Initiative and her partner Kiana Palacios are working with Ariele Baker under the DCRM Planning team, to come up with a long-term method to monitor the shoreline. So far, we came up with two ways to collect data about the shoreline which is surveying and beach profiling using the Berger Level. We have leveled all the beaches using existing elevations at benchmarks around the island. The other method is beach profiling which mainly focuses on the slope of the beach. We have sampled all the Western Beaches from south to north including Mańagaha. Kiana and I learned that is very important that we monitor the shoreline to see the changes. If our data shows that the beaches are eroding or growing, we must take action to find resolution before drastic effects may happen. Especially now that we are experiencing some sea level rise from climate change, we need data for future actions. My experience under this internship has been great. It has exposed me into a whole different field of environmental science and I am glad that it did. I see myself pursuing a degree in Natural Resource Management and perhaps becoming a Climate and Coastal Hazards Specialist. –Teisha Camacho

Early morning walks by the beach with swim wear outfits, water jug with ice and water, Berger leveler, waterproof camera, a rod, measuring tape, and some morning snacks (usually two vegetable lumpia) for my partner and I. The hot sun out shinning bright on our body making us darker than usual while we set our equipment up to start our day. Shoreline monitoring was fun. My partner and I were assigned to a project to monitor the shorelines of the Western beaches running from south to north including the island of Mańagaha which has five sections to it to monitor coastal erosion.

Measuring our land marks and about five to ten feet into the water requires a lot of walking up and down while my partner reads through the tripod and writes data down into our data sheets. You take this process and multiply it by three because we measuring the beginning, middle, and end of each beach which probably starts to build up our muscles by longs walks and carrying our equipment from one place to the other and back. We do these measurements to determine if we are going through coastal erosions and update our beach profiles. Some beaches have shown damages from coastal erosion like Sugar Dock, where the end point is broken into pieces leaving cracks in between the dock making it dangerous for our community to use or Micro beach where the side walk along the right side of the pavilion had collapsed. –Kiana Palacios

Sea Turtle Monitoring- Dan Kaipat, DLNR Sea Turtle Program Intern

Green sea turtles are endangered in our region. By working within the DLNR Turtle Program I was able to help conserve and work with turtles to assure them a better chance of survival. My job deals with conducting beach surveys, nest inventory, night tagging, and in-water tagging. Beach surveys are when we patrol beach areas to find turtle tracks and nests or signs of hatchling emergence. When we do nest inventories we count egg shells and sometimes find one or more live hatchlings who have not escaped, which we release immediately. Night tagging involves waiting patiently in the dark for female turtles to come on shore. Depending on the turtle, it can take several hours for a turtle to find good habitat in which to lay her eggs. After a turtle lays her eggs we tag her flippers, measure her shell, put a temperature data logger within the nest, and cover her tracks. In-water tagging is where we hand-capture turtles on the reefs and bring them to shore where we measure and tag each turtle. These measurements are used to record their size for data comparisons and to see how much they’ve grown the next time they are caught. The tags we insert in each turtle has a unique coded number which are used to track and gain valuable research data. After all our measurements and tagging are finished, the turtles are then released back into the water. As a Northern Marianas College Natural Resource Management program (NRM) student, this internship means a lot to me. In NRM we learn so much about the environment and endangered species. By working in this internship I was able to participate in different areas relating to our environment. I was able to get exposed to research field work and get hands on training and experience. This internship has opened my mind to many more areas of scientific interest, and has motivated me to continue with environmental studies.

Marine Invertebrate Harvesting-Mallory Muna, DFW Intern

My name is Mallory Muña and I am a Coral Reef Initiative Summer Intern with the Division of Fish & Wildlife. This summer I am assisting Fish & Wildlife biologists in a research study that aims to identify the potential impacts that new commercial developments and an increased tourism economy has on marine invertebrate species. My responsibilities for this project included writing and administering a human dimensions survey to local residents regarding marine invertebrate harvesting and consumption habits. Ultimately, this research will assist local agencies in establishing a comprehensive list of threatened marine invertebrate species, therefore allowing them to make informed management decisions. –Mallory Muna

“Let’s Protect What’s Ours” – Tanner Kenty, DCRM Enforcement Intern

Our island displays some of the best sunsets on Earth. They may not always be the same, but they are beautiful every time. What makes them even more fascinating is that when we look out to the sea, we see an unbelievably pristine ecosystem. So whom should we thank? Well, first and foremost, we should be thankful for picking up after ourselves, whether we are at the beach, or at home. Our small effort contributes to such a great cause, which is keeping our coastal resources clean and free. Secondly, we should be grateful to the men and women of the Division of Coastal Resource Management’s Enforcement team. Day in and day out, these guys and gal put so much effort in preventing any hazardous materials, whatever it may be, from damaging our streams, wetlands and ocean. So let’s help out one another and contact the enforcement team of DCRM @ (670) 588-2926, (670) 664-8300 or (670) 664-8500 to report any activity that you assume may be threatening to our coastal resources. In addition, a Reef Report App is available for you to report violations using your mobile device or computer. Hopefully, our efforts would allow future generations to enjoy the beauty of our island and its sunsets as we do. -Tanner Kenty

2015 CRI Summer Interns’ Conservation Messages

We had a great time this summer with the 2015 Coral Reef Initiative internship participants! This summer14 interns held various positions with DFW, BECQ-CRM, MINA, DLNR, and NOAA learning about the various ways our government and partners work to protect CNMI’s precious natural resources.

Check out this fun video of the CRI intern cohort (and CNMI Micronesia Challenge Young Champion Carey Demapan) during a field trip to the Managaha Marine Conservation Area! How many of these bright young CNMI stars do you know or recognize?

The video was compiled and edited by CRI intern Romana Chong. Original song by Nikkie Ayuyu

(Photo below is a link.)

2015 CRI SUMMER INTERNS:

- Delfin Camacho – worked with DCRM Enforcement, monitoring enforcement and compliance of permitted projects and marine sports activities.

- Miso Sablan and Andrew Johnson – Conducted reef flat surveys looking for signs of coral disease with the CNMI Marine Monitoring Team based at BECQ.

- Nikkie Ayuyu and Anathalia David – conducted marine debris education outreach and research, with MINA (Micronesia Islands Nature Alliance – a key partner NGO).

- Erick Dela Rosa and Max Garcia – worked with the DLNR Sea Turtle team conducting nest surveys and monitoring as well as in-water live capture and tagging of sea turtles.

- Kallie O’Conner, Jacklyn Garote, Romana Chong – Designed and assisted in implementation of various MPA education and outreach strategies, with the MPA Coordinator based at DFW.

- Austin Piteg and Mary Fem Urena – worked with the CNMI NOAA field office staff conducting water quality and seagrass monitoring along the length of the Saipan lagoon.

- Eric Cepeda and Ian Iriarte – Worked with DFW fisheries department on various fishery biology and tourist –interaction projects.

2014 CRI INTERNS

2013 CRI INTERNS

Amber

The Garden That Can Save Our Ocean

Let’s think about how water travels after a rainstorm. It rolls down hills, picks up loose dirt and sediment, finds its way across pig farms and streets full of car oil, and then eventually ends up in our ocean. Would you want to swim in that? Didn’t think so. Our oceans are a sacred part of our lives, both culturally and economically. Luckily, there is a way to mitigate this problem that both homeowners and businesses can turn to: rain gardens. Rain gardens are gardens that are specifically placed to help slow down, collect, and filter polluted rainwater. They are attractive and can even increase biodiversity of your landscape. Instead of the rainwater going straight into our ocean, water can be collected in rain gardens and given time to filter into the ground, which can benefit the health of our ecosystem. For examples of local rain gardens, check out the rain garden at the CNMI Museum, right along Middle Road. Contact DEQ for more information about rain gardens and how you can install one at your own home or business.

Let’s think about how water travels after a rainstorm. It rolls down hills, picks up loose dirt and sediment, finds its way across pig farms and streets full of car oil, and then eventually ends up in our ocean. Would you want to swim in that? Didn’t think so. Our oceans are a sacred part of our lives, both culturally and economically. Luckily, there is a way to mitigate this problem that both homeowners and businesses can turn to: rain gardens. Rain gardens are gardens that are specifically placed to help slow down, collect, and filter polluted rainwater. They are attractive and can even increase biodiversity of your landscape. Instead of the rainwater going straight into our ocean, water can be collected in rain gardens and given time to filter into the ground, which can benefit the health of our ecosystem. For examples of local rain gardens, check out the rain garden at the CNMI Museum, right along Middle Road. Contact DEQ for more information about rain gardens and how you can install one at your own home or business.

Daphne

Beach Atlas

Sea level rise, climate change, erosion, and much more may be a problem to our island and this is why we are creating a beach atlas. A beach atlas is very important to have anywhere that has to deal with waters surrounding a location. Saipan’s beach atlas will be a map of Saipan’s shorelines that can be updated annually to show changes in the shorelines. The data we have collected at beaches around Saipan is being compared to how beaches were in the nineties. Managaha in the nineties experienced many changes from sea level rise to parts of the island breaking off, whereas Susupe Beach Park shrunk in size. The purpose of this project is so Saipan residents will know about climate change and sea level rise threats. My coworker and I started working on our beach atlas project at the start of the summer and have made fast progress in collecting information from over 10 beaches on Saipan. The information we gathered from the beaches includes: beach widths, sediment size, weather, tide levels, and signs of accretion, and erosion. “There is potential for the sea level to rise by three feet in the CNMI over the next 75-100 years. Understanding where the problems with natural processes are now will help us identify where problems will worsen in the future,” stated Robbie Greene, mentor and NOAA Coastal Fellow. I’m positive to say that the Saipan beach atlas we are creating will be an annual project because this is something that should and will be worked on yearly.

Sea level rise, climate change, erosion, and much more may be a problem to our island and this is why we are creating a beach atlas. A beach atlas is very important to have anywhere that has to deal with waters surrounding a location. Saipan’s beach atlas will be a map of Saipan’s shorelines that can be updated annually to show changes in the shorelines. The data we have collected at beaches around Saipan is being compared to how beaches were in the nineties. Managaha in the nineties experienced many changes from sea level rise to parts of the island breaking off, whereas Susupe Beach Park shrunk in size. The purpose of this project is so Saipan residents will know about climate change and sea level rise threats. My coworker and I started working on our beach atlas project at the start of the summer and have made fast progress in collecting information from over 10 beaches on Saipan. The information we gathered from the beaches includes: beach widths, sediment size, weather, tide levels, and signs of accretion, and erosion. “There is potential for the sea level to rise by three feet in the CNMI over the next 75-100 years. Understanding where the problems with natural processes are now will help us identify where problems will worsen in the future,” stated Robbie Greene, mentor and NOAA Coastal Fellow. I’m positive to say that the Saipan beach atlas we are creating will be an annual project because this is something that should and will be worked on yearly.

Julius

CNMI Marine Monitoring Team

The goal of CNMI’s long-term coral reef monitoring program is to provide the information necessary for the wise management of our precious reef resources. We document how reef communities change over time in response to natural environmental fluctuations as well as those caused by people. Julius Reyes, an intern under the Coral Reef Initiative is working with MMT and is studying variations of algae species and invertebrates at beach sites with submarine groundwater discharge or SGD’s, which are fresh water streams that occur on the shores in our lagoon. I will be comparing sites with SGD to beaches without SGD’s. SGD’s can carry nitrogen in its streams. The ocean has a minimal amount of nitrogen, also known as being nitrogen limited. Algae thrive in ocean water where the nitrogen levels are higher, like estuaries, or on the shore where SGD occurs. Algae populations can detrimentally harm coral reefs by blocking out sunlight essential to the growth of corals. People from all over the world come to Saipan to dive and enjoy the coral reefs, therefore we must do all we can to protect them.

The goal of CNMI’s long-term coral reef monitoring program is to provide the information necessary for the wise management of our precious reef resources. We document how reef communities change over time in response to natural environmental fluctuations as well as those caused by people. Julius Reyes, an intern under the Coral Reef Initiative is working with MMT and is studying variations of algae species and invertebrates at beach sites with submarine groundwater discharge or SGD’s, which are fresh water streams that occur on the shores in our lagoon. I will be comparing sites with SGD to beaches without SGD’s. SGD’s can carry nitrogen in its streams. The ocean has a minimal amount of nitrogen, also known as being nitrogen limited. Algae thrive in ocean water where the nitrogen levels are higher, like estuaries, or on the shore where SGD occurs. Algae populations can detrimentally harm coral reefs by blocking out sunlight essential to the growth of corals. People from all over the world come to Saipan to dive and enjoy the coral reefs, therefore we must do all we can to protect them.

Keena

Napoleon (Humphead) Wrasse

On June 24, Mariana Islands Nature Alliance (MINA) welcomed its Coral Reef Initiative intern, Keena Leon Guerrero. As part of her summer internship, Keena was assigned an exciting project involving the Napoleon Wrasse (also known as the humphead wrasse), a large, majestic fish that can live up to 30 years, grow up to six and a half feet, and weigh up to 400 pounds. It is also one of the few species of fish that willingly associates with humans, making it likeable to divers and tourists worldwide. The humphead wrasse has many more unique characteristics, including the fact that it is one of the only species in the world that is able to eat the crown of thorns starfish- a venomous starfish that damages the coral it feasts on. The overall purpose of Keena’s project is to educate the general public on the importance of the Napoleon Wrasse and explain why we should protect it. This would involve creating outreach material explaining what the Napoleon Wrasse is, what is threatening it, and why it should be protected. To learn more information on the Napoleon Wrasse, visit the website: http://www.minapacific.org

On June 24, Mariana Islands Nature Alliance (MINA) welcomed its Coral Reef Initiative intern, Keena Leon Guerrero. As part of her summer internship, Keena was assigned an exciting project involving the Napoleon Wrasse (also known as the humphead wrasse), a large, majestic fish that can live up to 30 years, grow up to six and a half feet, and weigh up to 400 pounds. It is also one of the few species of fish that willingly associates with humans, making it likeable to divers and tourists worldwide. The humphead wrasse has many more unique characteristics, including the fact that it is one of the only species in the world that is able to eat the crown of thorns starfish- a venomous starfish that damages the coral it feasts on. The overall purpose of Keena’s project is to educate the general public on the importance of the Napoleon Wrasse and explain why we should protect it. This would involve creating outreach material explaining what the Napoleon Wrasse is, what is threatening it, and why it should be protected. To learn more information on the Napoleon Wrasse, visit the website: http://www.minapacific.org

Kyanna

Beach Atlas

The purpose of a beach atlas is to have a map of Saipan’s shorelines that can be updated annually to show changes. This is important because recorded changes can help predict future changes to Saipan shores which could have potentially negative effects on the people and wildlife. A project such as this is important to the people of the CNMI as a whole, because it affects us all. Before making a beach atlas, data must be gathered by going to each of Saipan’s beaches to take measurements and pictures. Measuring tape is used to record the width of the beach and the grain size of the sand. Pictures of the beaches help scope out indicators of erosion and accretion as well as things that might be affecting the beach. All of this data is gathered together to create the final result, which is the beach atlas.

The purpose of a beach atlas is to have a map of Saipan’s shorelines that can be updated annually to show changes. This is important because recorded changes can help predict future changes to Saipan shores which could have potentially negative effects on the people and wildlife. A project such as this is important to the people of the CNMI as a whole, because it affects us all. Before making a beach atlas, data must be gathered by going to each of Saipan’s beaches to take measurements and pictures. Measuring tape is used to record the width of the beach and the grain size of the sand. Pictures of the beaches help scope out indicators of erosion and accretion as well as things that might be affecting the beach. All of this data is gathered together to create the final result, which is the beach atlas.

Melanie

Nonpoint Source Pollution (NPS)

Many understand the definition of pollution, but do they understand what non-point source pollution really is? Nonpoint Source Pollution (NPS) is defined as any source of water pollution such as runoff, toxic chemicals such as motor oil, pesticides and fertilizers; this type of pollution greatly affects our land and our sea. For example, during rainfall exposed soil from home gardens or farms gets washed away along with trash and chemicals that are on the ground. All of these eventually find their way into the ocean which endangers the health of our marine life and our coral reefs. Living on an island, we rely on our beaches and coral reefs for food and tourism so it is important for us to care for our natural resources and its inhabitants. Campaigns such as RARE, Think Blue and Our Laolao are designed to educate the public on the importance of our natural resources and how to preserve their health and beauty. My project is to create education and outreach materials designed to help increase knowledge and awareness within the community about NPS. Just remember that what happens on land affects our sea. Protection is key to sustainability so that future generations may enjoy our beautiful island resources as well.

Many understand the definition of pollution, but do they understand what non-point source pollution really is? Nonpoint Source Pollution (NPS) is defined as any source of water pollution such as runoff, toxic chemicals such as motor oil, pesticides and fertilizers; this type of pollution greatly affects our land and our sea. For example, during rainfall exposed soil from home gardens or farms gets washed away along with trash and chemicals that are on the ground. All of these eventually find their way into the ocean which endangers the health of our marine life and our coral reefs. Living on an island, we rely on our beaches and coral reefs for food and tourism so it is important for us to care for our natural resources and its inhabitants. Campaigns such as RARE, Think Blue and Our Laolao are designed to educate the public on the importance of our natural resources and how to preserve their health and beauty. My project is to create education and outreach materials designed to help increase knowledge and awareness within the community about NPS. Just remember that what happens on land affects our sea. Protection is key to sustainability so that future generations may enjoy our beautiful island resources as well.

Mon

Loan a Box of Knowledge

Times are changing, along with the environment. Coastal Resources Management (CRM) has been developing a loan box, or as we call it, treasure chests. They include all sorts of creative games and activities, ranging from crossword puzzles to animal crafts to fishing games. It is designed to be used as both an educational and entertaining tool for kids. Teachers around the CNMI will be able to rent these boxes to supplement and enhance their teaching plans in a range of subject areas. Boxes are free to rent and can be checked out through CRM. Be part of the movement by educating yourself and others on matters that affect our islands. You can start small in helping the environment just by renting these treasure chests full of knowledge.

Times are changing, along with the environment. Coastal Resources Management (CRM) has been developing a loan box, or as we call it, treasure chests. They include all sorts of creative games and activities, ranging from crossword puzzles to animal crafts to fishing games. It is designed to be used as both an educational and entertaining tool for kids. Teachers around the CNMI will be able to rent these boxes to supplement and enhance their teaching plans in a range of subject areas. Boxes are free to rent and can be checked out through CRM. Be part of the movement by educating yourself and others on matters that affect our islands. You can start small in helping the environment just by renting these treasure chests full of knowledge.

Nemi

Shark Education for Everyone

Shark species are decreasing rapidly to about 73 million each year due to shark fining and that is why I am working on educating the public and local department stores/businesses here on Saipan about this issue. This outreach is important for everyone from kids and adults to fishermen and business owners. The purpose of this project is to educate the people of Saipan about the problems we could face with a decreasing shark population and possible effects on the oceans environment. I am requesting that businesses and store owners eliminate certain products that contain shark ingredients from their shelves and cease future purchasing of these products. This project is important because it supports the Shark Conservation Act 17-27 that was established here in the CNMI. I started working on this project on the 24th of June and I hope to educate the public and share my interest to make a difference in our environment by simply being responsible for our actions in our environment.

Shark species are decreasing rapidly to about 73 million each year due to shark fining and that is why I am working on educating the public and local department stores/businesses here on Saipan about this issue. This outreach is important for everyone from kids and adults to fishermen and business owners. The purpose of this project is to educate the people of Saipan about the problems we could face with a decreasing shark population and possible effects on the oceans environment. I am requesting that businesses and store owners eliminate certain products that contain shark ingredients from their shelves and cease future purchasing of these products. This project is important because it supports the Shark Conservation Act 17-27 that was established here in the CNMI. I started working on this project on the 24th of June and I hope to educate the public and share my interest to make a difference in our environment by simply being responsible for our actions in our environment.

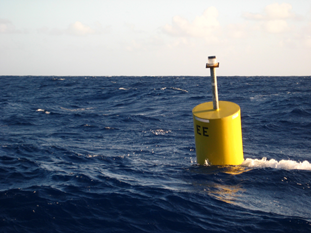

Phil

Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs)

Many people do not quite understand what the role of the fisheries division is, they help the people achieve more when it comes to fishing. One of the major projects to help local fishermen is the fish aggregating device (FAD) project, which will have a great impact on fish production. FAD’s are basically just buoys that float in certain areas around the CNMI. Fish use these buoys as shelter from predators and also to help them navigate around the ocean. It also makes the fishermen focus on a fixed location to fish instead of travelling farther and catching smaller amounts. Some other projects include dissecting and tagging fish. There are two types of fish we dissect, Parrotfish and Kali Kali. The parrotfish samples come from local fish markets and the Kali Kali is caught by DFW employees. The types of fish we tag are Mafute, which we also collect ourselves. We head out at least once every week and are lucky to tag two or more every time because they are hard to catch in the afternoon. We tag and dissect these fish so that we can get an overall production rate annually and also to know the average size being caught by the fishermen. For instance, if the average size being caught every year drops, the fisheries division would recommend not catching a certain fish until it’s at a certain size. Working here has given me a greater insight on biology, sea ecosystems and why we should help preserve it.

Many people do not quite understand what the role of the fisheries division is, they help the people achieve more when it comes to fishing. One of the major projects to help local fishermen is the fish aggregating device (FAD) project, which will have a great impact on fish production. FAD’s are basically just buoys that float in certain areas around the CNMI. Fish use these buoys as shelter from predators and also to help them navigate around the ocean. It also makes the fishermen focus on a fixed location to fish instead of travelling farther and catching smaller amounts. Some other projects include dissecting and tagging fish. There are two types of fish we dissect, Parrotfish and Kali Kali. The parrotfish samples come from local fish markets and the Kali Kali is caught by DFW employees. The types of fish we tag are Mafute, which we also collect ourselves. We head out at least once every week and are lucky to tag two or more every time because they are hard to catch in the afternoon. We tag and dissect these fish so that we can get an overall production rate annually and also to know the average size being caught by the fishermen. For instance, if the average size being caught every year drops, the fisheries division would recommend not catching a certain fish until it’s at a certain size. Working here has given me a greater insight on biology, sea ecosystems and why we should help preserve it.

Rich

Fish Sampling

Understanding the main concepts of fish anatomy has really given me a great perspective on what biologist do to obtain samples. Dissecting Parrotfish and Kali Kali were some of the main samplings I had to do. The purpose for dissecting these fishes are to find their maturity and reproduction growth in the CNMI. Not only do we dissect fish, but we also look at their habitats, such as sea grass areas. Our project is to take underwater video footage of sea grass areas while also recording the number of juvenile fish we see along the transect line. From our first transect, we found that certain fish migrate to a specific area, while other fish tend to roam freely to find food. The average size fish recorded was about 2-3 inches long and was found around the sea grass areas. Many of the fish we found were the juvenile fish trevallies. We will be continuing this project and are looking forward to see more fish around the Western side of Saipan. The reasons why we collect data are to provide information to biologist/researchers and others for use in program planning and management. My experiences here have greatly helped me fulfill my expectations on my future career and I look forward learning more about what the fisheries section do.

Understanding the main concepts of fish anatomy has really given me a great perspective on what biologist do to obtain samples. Dissecting Parrotfish and Kali Kali were some of the main samplings I had to do. The purpose for dissecting these fishes are to find their maturity and reproduction growth in the CNMI. Not only do we dissect fish, but we also look at their habitats, such as sea grass areas. Our project is to take underwater video footage of sea grass areas while also recording the number of juvenile fish we see along the transect line. From our first transect, we found that certain fish migrate to a specific area, while other fish tend to roam freely to find food. The average size fish recorded was about 2-3 inches long and was found around the sea grass areas. Many of the fish we found were the juvenile fish trevallies. We will be continuing this project and are looking forward to see more fish around the Western side of Saipan. The reasons why we collect data are to provide information to biologist/researchers and others for use in program planning and management. My experiences here have greatly helped me fulfill my expectations on my future career and I look forward learning more about what the fisheries section do.

Thomas

Don’t Feed Fish

The DFW Enforcement section continues to provide education and outreach to the users at Managaha Marine Protected Area. As much as it may enhance a tourist attraction, feeding fish regularly, can be harmful to the marine ecosystem at Managaha Marine Protected Area (Sanctuary). This can be seen through the fish behavior towards humans. The fish at Managaha are observed to be more aggressive compared to other beaches on the island. One of the most apparent fish behaviors at Managaha Marine Protected area is the swimming towards people in the water. This behavior makes the fish dependent on the tourist feeding them, rather than getting their own food which are algae, plankton and other small fish. Fish provide an important role in the marine ecosystem by reducing algae cover on coral reefs and maintaining a balance in fish population and the marine environment.

The DFW Enforcement section continues to provide education and outreach to the users at Managaha Marine Protected Area. As much as it may enhance a tourist attraction, feeding fish regularly, can be harmful to the marine ecosystem at Managaha Marine Protected Area (Sanctuary). This can be seen through the fish behavior towards humans. The fish at Managaha are observed to be more aggressive compared to other beaches on the island. One of the most apparent fish behaviors at Managaha Marine Protected area is the swimming towards people in the water. This behavior makes the fish dependent on the tourist feeding them, rather than getting their own food which are algae, plankton and other small fish. Fish provide an important role in the marine ecosystem by reducing algae cover on coral reefs and maintaining a balance in fish population and the marine environment.

Yoshi

Box Jellies

Have you ever heard of a “Box Jellyfish”? Have you ever been stung by one? Chances are you haven’t. Still, it’s good to know things about these cubozoan critters, since contact with them tends to leave you in pain. Dr. Angel Yanagihara, a world renowned researcher in the field of Box Jellyfish (Cubozoans) from the University of Hawaii, recently embarked on a trip to Saipan to attempt to find the nearly invisible creatures. She confirmed the presence of Box Jellyfish around Saipan, yet still very little is known about the jellyfish we have here. The Pacific Marine Resources Institute (PMRI) and their Coral Reef Initiative intern, Yoshi Yagi, are working on finding out more about box jellyfish in Saipan. How prevalent are box jellies in our islands? Are their population numbers increasing, decreasing, or stable? How many people have ended up in the Emergency Room because of box jellyfish stings? Can we predict the next time the jellies will arrive on our shores? Answering these questions will help safeguard both tourists and residents alike from a painful sting. In order to further our research PMRI is requesting fishermen, lifeguards, tour guides, and anyone who might have any information on the box jellyfish to assist us. Please contact 233-7333 for more information or to schedule an interview.

Have you ever heard of a “Box Jellyfish”? Have you ever been stung by one? Chances are you haven’t. Still, it’s good to know things about these cubozoan critters, since contact with them tends to leave you in pain. Dr. Angel Yanagihara, a world renowned researcher in the field of Box Jellyfish (Cubozoans) from the University of Hawaii, recently embarked on a trip to Saipan to attempt to find the nearly invisible creatures. She confirmed the presence of Box Jellyfish around Saipan, yet still very little is known about the jellyfish we have here. The Pacific Marine Resources Institute (PMRI) and their Coral Reef Initiative intern, Yoshi Yagi, are working on finding out more about box jellyfish in Saipan. How prevalent are box jellies in our islands? Are their population numbers increasing, decreasing, or stable? How many people have ended up in the Emergency Room because of box jellyfish stings? Can we predict the next time the jellies will arrive on our shores? Answering these questions will help safeguard both tourists and residents alike from a painful sting. In order to further our research PMRI is requesting fishermen, lifeguards, tour guides, and anyone who might have any information on the box jellyfish to assist us. Please contact 233-7333 for more information or to schedule an interview.

Zabrina

CNMI Making a Difference in Sea Turtle Conservation

Sea turtles have been around for millions of years and they’ve played a big role in maintaining and contributing in a variety ways to the oceans ecosystems. These creatures are becoming endangered and their numbers are dropping fast due to many anthropogenic or human related impacts. Their main threats are accidental capture or by-catch, coastal developments, illegal harvest, and global warming. The CNMI’s DLNR Division of Fish and Wildlife Sea Turtle Program (STP) have taken a dive in to the pacific seas to gain more information on the sea turtles that inhabit the CNMI waters. The goals of the STP are to protect, monitor and collect important data and information on these ancient creatures and share what is gained with the community and the rest of the world. Every little effort counts when dealing with conservation of the planets wildlife and natural resources. The CNMI is but a tiny spec on the globe; with strong efforts the STP is making a difference in keeping our coral reefs healthy and helping to regain sea turtle population on our side of the earth.

Sea turtles have been around for millions of years and they’ve played a big role in maintaining and contributing in a variety ways to the oceans ecosystems. These creatures are becoming endangered and their numbers are dropping fast due to many anthropogenic or human related impacts. Their main threats are accidental capture or by-catch, coastal developments, illegal harvest, and global warming. The CNMI’s DLNR Division of Fish and Wildlife Sea Turtle Program (STP) have taken a dive in to the pacific seas to gain more information on the sea turtles that inhabit the CNMI waters. The goals of the STP are to protect, monitor and collect important data and information on these ancient creatures and share what is gained with the community and the rest of the world. Every little effort counts when dealing with conservation of the planets wildlife and natural resources. The CNMI is but a tiny spec on the globe; with strong efforts the STP is making a difference in keeping our coral reefs healthy and helping to regain sea turtle population on our side of the earth.